Talk:Sanskrit Language Origin

By Swami Harshananda

Origin[edit]

How a language—any language for the matter—could attain the present degree of sophistication and artistry, start¬ing with a physical sign language and inarticulate babble is a mystery. It is a mystery that linguistics or phonetics or etymology or philology will never be able to solve!

Hinduism, however, has easily ‘solved’ the same by attributing the origin of all languages and sciences to God Himself! An interesting verse in an ancient work called Nandikeśvarakārikā declares that all the alphabets of the Sanskrit language (and hence its grammar) have evolved out of the fourteen sounds made by Lord Siva through his ḍamaru (a small drum held in hand for making sounds), at the end of his cosmic dance.

Two Divisions[edit]

Though Sanskrit is called devabhāṣā —the language of the gods in heaven—in practice it is divided into two categories: the vaidika (Vedic) and the laukika (secular).

The Vedas, the Vedāṅgas, the Upavedas and allied literature belong to the first group. All the other literature from the itihāsas and purānas right up to the modern Sanskrit literature—falls under the second group.

Vedic Literature[edit]

The earliest form of Sanskrit is that of the Rgveda. According to the orthodox Hindu tradition, the entire body of the Vedic mantras (known as the Saiñhitās) was, originally, one mass. The sage Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana collected all these Vedic mantras and divided them into four groups as per the needs of sacrificial religion that was in vogue. Hence he was called Vedavyāsa or Vyāsa. The four groups are: Rk, Yajus, Sāma and Atharva. In course of time three more sections were gradually added to each of the four Vedas. They are: Brāhmaṇa, Āraṇyaka and Upaniṣad. (For details see VEDAS.) Since the language of the Vedas was archaic and the concepts were slowly becoming obsolescent, explanatory works became necessary. This resulted in the production of the six Vedāṅgas (limbs or subsidiary works). They are: Sikṣā (phonetics); Vyākaraṇa (grammar); Chandas (prosody); Nirukta (etymology); Jyautiṣa (astronomy); and, Kalpa (practi¬cal method). The four Upavedas (subsidiary Vedas) viz., Ayurveda (health-sciences), Dhanur- veda (military science), Gāndharvaveda (science of music and fine-arts) and Artha- śāstra (political science), are also some¬times included under the Vedic literature. Various anukramaṇīs (works similar to an index) by authors such as Saunaka and Kātyāyana may also be classed under the Vedic literature.

Itihāsas and Purānas[edit]

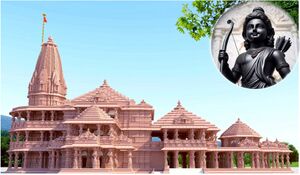

Rāmāyana of Vālmiki and the Mahābhārata of Vyāsa are known as the itihāsas. They contain ancient history as also plenty of religio-philosophical teach¬ings. (See MAHĀBHĀRATA and RĀMĀYANA for details.) The original basic material of the purāṇas—known as the Purāṇasamhitā— is as old as the Vedas. Over the centuries, it gradually took the took the shape of the present purāṇas and upapurāṇas (each group containing eighteen works). (See PURĀNAS.) Of these, the Visnupurāna and the Bhāga- vata are considered important.

Classical Sanskrit Literature[edit]

There was a gradual evolution of the Sanskrit language from the archaic form of the Saiñhitās to the classical form, first through the Brāhmaṇas and then through the epics. This vast and varied literature— both in content and in methodology—may now be summarised very briefly, as fol¬lows, arranging them in the English alphabetical order for convenience:

ALANKĀRASĀHITYA[edit]

It is the science of figure of speech. The Nātyaśāstra of Bharata (200 B. C.) seems to be the earliest attempt at systematisation of poetics and dramaturgy. However, it is the well-known authors like Bhāmaha and Daṇḍin (6th century A. D.), Ānandavardhana (9th century A. D.) and Mammaṭa (11th century A. D.) who have contributed much to the development of this science. They were also responsible for the evolution of several sampradāyas or schools. (See ALANKĀRAŚĀSTRA.)

CAMPU SĀHITYA[edit]

there is a balanced combination of elegant prose and poetry, each embellishing the other. The Vedic ākhyānas might have laid the foundation to the later campu- literature. The extant campukāvyas belong to a period later than the 9th century A. D. The following is a list of some of the more well-known works belonging to the campu literature: Nalacampu of Trivikramabhaṭṭa; Campurāmāyana of Bhoja; Bhāgavata- campu by Abhinava Kālidāsa; Nllakantha- vijayacampu of Nīlakaṇthadikṣita; Viśva- gunādarśacampu of Veṅkaṭādhvarin.

DARŚANAŚĀSTRAS[edit]

Philosophical schools are known as darśanas. The three heterodox schools (Cārvāka, Jaina and Bauddha) and the six orthodox schools (Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Sāṅkhya, Yoga, Mīmārhsā and Vedānta) as also several others have produced a voluminous literature in the form of sutras and commentaries as also independent works. It is the Brahmasutras of Bādarāyaṇa that has induced the maximum number of works.

GADYASĀHITYA[edit]

Earliest specimens of available prose go back to the era 3000 B. C., the age of the Brāhmaṇas. Some of the Upaniṣads like the Chāndogya and the Brhadā- ranyaka which are mostly in prose, go back to the same or an even earlier period. In the sutra-period also we come across prose in the form of the bhāsyas or commentaries, some of which are quite elegant. Literary prose must have been popu¬lar even in ancient times as mentioned by Patañjali in his Mahābhāśya on the Astādhyāyi. They are the ākhyāyikās (stories) connected with Vāsavadatta,Sumanottara and others. Depending on the style of writing, these prose works of the literary or classical type are divided into three groups: romances; popular tales; didactic fables. The following works may be cited as examples of exquisite prose compositions: Daśakumāracarita of Daṇḍin; Kādambarī of Bāṇa; Vāsavadatta of Subandhu; Tilakamañjari of Dhanapāla; Gadya- cintāmanl of Oḍeyadeva.

KATHĀSĀHITYA[edit]

Sanskrit literature did not lag behind in the creation and propagation of stories. These stories were composed not only to reflect the nature of the contemporary society but also keep some great ideals before it. Though the Vedic literature has stories in the form of ākhyānas, a serious attempt to compile a single volume, only of stories, is first found in the Brhatkathā in the Paiśācī language (a distorted version of Sanskrit). The Kathāsaritsāgara of Somadeva (11th century A. D.) is said to be a faithful translation of the Brhatkathā, the original of which is not available. The Brhatkathāmañjarī of Kṣemendra is an earlier attempt of the same type. The other reputed works in this field are:

KĀVYASĀHITYA[edit]

Sanskrit literature is replete with kāvyās or poetical works of the highest quality. Starting with the Rāmāyana of Vālmīki as the earliest in the series— rightly called the Ādikāvya—there has been a galaxy of great poets and their works. A very brief list of their names and some of their works may now be given;

KĀUDĀSA[edit]

(100 B. C.) His poetical works are: Kumārasambhava; Meghaduta; Raghu- vamśa; Rtusamhāra. Out of these, the Raghuvamśa has forty commentaries, the Sañjīvinī of Mallinātha being the best.

BHĀRAVI[edit]

(450 A. D.) Kirātārjurdya is his only work.

BHATTI[edit]

5th century A. D.) The Bhattikāvya (also known as Rāvanavadha) is his only work. Along with beautiful poetry, this work tries to make Sanskrit grammar easy for the students of that subject.

MĀGHA[edit]

(A. D. 650) His magnum opus and the only work is the Siśupālavadha. It has eight commentaries out of which the Sandeha- visausadhi of Vallabha (A. D. 940) is the best.

KSEMENDRA[edit]

(birth A. D. 1000) Though nineteen works have been authored by him, mention may be made only of two poetical works: Rāmāyana- mañjari and Bhāratamañjari. These are brief works but elegant.

ŚRĪHARSA[edit]

(12th century A. D.) Out of his nine works, the Naisa- dhiyacarita dealing with the story of Nala and Damayantī is considered the best. He also wrote a highly polemical work on Advaita Vedānta called Khandana- khanda-khādya, which reflects his erudi¬tion in that branch.

VEDĀNTA DEŚIKA[edit]

(A. D. 1268-1369) Though well-known as a prolific and scholarly writer on Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta, Vedānta Deśika was also a great litter¬ateur. Special mention should be made of his two works: Yādavābhyudaya and Hamsasandeśa. The former contains the story of Kṛṣṇa whereas the latter deals with that of Rāma and Sītā, especially the sorrow of their separation.

NĀTAKASĀHITYA[edit]

There is enough evidence—like the Samvādasuktas of the Rgveda—to prove that nātakas or dramas have existed since the most ancient times. The epics contain references to dances, dramas and theatres. Bharata’s Natyaśāstra was the earliest treatise on dramaturgy. Now, a list of well-known authors of nāṭakas and their works may be given:

BHĀSA[edit]

Earliest of the playwrights, Bhāsa might have lived during the period 500 to 400 B.C. The dramas attributed to him are thirteen. Out of these mention may be made of the following:

KĀLIDĀSA[edit]

(100 B. C.) The three well-known dramas of Kālidāsa are: Mālavikāgnimitra\ Vikra- morvaśīya and Abhijñānaśākuntala. The last has been considered the very best of all Sanskrit dramas. It is woven round the love between the king Duṣyanta and the damsel Sakuntalā of divine beauty.

VIŚĀKHADATTA[edit]

(7th century A. D.) The Mudrārāksasa is his magnum opus though two more dramas were composed by him. How Cāṇakya, the famous kingmaker and prime-minister of Candragupta Maurya won over Rākṣasa, the loyal premier of the Nandas and made him agree to be the prime-minister of Candra¬gupta Maurya is the main theme of this work.

ŚUDRAKA[edit]

(5th century A. D.) Sudraka was perhaps a king. His only work is the Mrcchakatikā (‘the mud-cart’). It is in ten acts and concerns mainly with the story of love between Vasantasenā (a prostitute of high culture) and Cārudatta a decent brāhmaṇa of noble character. The drama is replete with Prākṛt words also.

ŚRĪHARSHA or HARSAVARDHANA[edit]

The well-known emperor Srīharṣa or Harṣavardhana ruled at Sthāṇeśvara from A. D. 606 to 647. He was not only a great king but also an erudite author. Ratnāvali, Nāgānanda and Priya- darśikā are the three dramas authored by him.

BHATTANĀRĀYANA[edit]

(7th century A. D.) The Venisamhāra, a six-act play drawing its material from the Mahābhārata, is his only work. Bhīma’s character has been highlighted and represented ably.

BHAVABHUTI[edit]

(8th century A. D.) He is considered almost equal to Kālidāsa as to the qualities of his dramas which are three: Mālatimādhava Mahāvīracarita and Uttararāmāyana. He was also well-versed in the philosophical lore. It is the last, in seven acts, that is more famous. It draws the story from the Uttarakānda of the Rāmāyana making some interesting changes in the original story to enhance the literary grace of the work. Apart from these, there have been a few more less-known playwrights such as Murāri (8th century A. D.; Anarghya- rāghava), Rājaśekhara (circa A. D. 900; Bālarāmāyana, Bālabhārata and Karpura- mañjari), Saktibhadra (9th century A. D.; Āścaryacudāmanī) and Jayadeva (13th century A. D.; Prasannarāghava).

NIGHANTU[edit]

Nighaṇṭu means a dictionary. The first ever dictionary in Sanskrit is the Nighantu, an ancient dictionary of Vedic words by an unknown author. The Nirukta of Yāska (800 B. c.) is a commentary on this Nighantu. Till now 87 Sanskrit dictionaries have been traced and found to have existed. Only, very few of them have been printed so far. The Nāmalingānuśāsanam of Amara Simha (A. D. 500), more popularly known as the Amarakośa, is the best of Sanskrit dictionaries. It has 38 commentaries. (See AMARAKOŚA for details.) Some of the other dictionaries worth mentioning are: Liñgānuśāsana of Vyāḍi; Trikāndakośa of Bhāguri; Sabdārnava of Vācaspati; Hārāvalī of Puruṣottamadeva; Abhidhānaratnamālā or Halāyudhakośa of Halāyudha; Nānārthaśabdakośa or Medinlkośa of Medinīkara; Kalpadruma- kośa of Keśava; Sabdakalpadruma of Rādhākāntadeva; Vācaspatya of Tārā- nātha-tarka-vācaspati and Nānārthār- navasañksepa of Keśavasvāmin.

PURĀNASĀHITYA[edit]

Starting with the ākhyāyikās or stories carried over from the ancient (pre-Vedic) days, the purāṇa literature has now grown into a huge mass comprising the eighteen Mahāpurāṇas and the eighteen (or even more) Upapurāṇas. (See PURĀNAS for details.)

STOTRASĀHITYA[edit]

The stotrasāhitya or hymnal litera¬ture in Sanskrit is almost limitless. Great mystics and devotee-poets, in their moments of divine ecstasy have burst forth into innumerable hymns. These hymns are in various poetical metres and contain a variety of feelings and descrip¬tions. They are addressed to the different deities of the Hindu pantheon such as Śiva, Devi, Viṣṇu, Gaṇapati, Subrahmaṇya and others. Mention may now be made of a small fraction of these hymns. They are: Sivamahimnastotra of Puṣpadanta; Saundaryaharl of Saṅkara; Mukundamālā of Kulaśekhara; Stotraratna of Yāmuna; Krsnakarnāmrta of Līlāśuka; Pādukā- sahasra of Vedānta Deśika; Laksml- sahasra of Veṅkaṭādhvari; Nārāyaniyam of Nārāyaṇa Bhaṭṭatiri; Dvādaśastotra of Madhva; Mukapañcaśatī of Mṅkakavi; and, Ānandasāgarastava of Nīlakaṇṭha- dīkṣita. Apart from this, the epics and the purāṇas too contain a legion of exquisitely beautiful hymns, some of which like the Visnusahasranāma, the Lalitāsahasra- nāma, the Adityahrdaya and the Durgā- saptaśatī have acquired the status of potent mantras. They are extremely popular even now.

SUKTISĀHITYA[edit]

A sukti or a subhāṣita (= good-saying; wise statement) is like a popular maxim or proverb. It contains the quintessence of the experience of a whole race over several generations. The Sanskrit language is full of such sayings. They are found interspersed almost in every branch of the literature. However, several scholars have made serious attempts to bring these sayings together in an organised manner. The following is the list of some of the better-known compilations: Subhāsita- ratnakośa of Vidyādhara; Subhāsitāvali of Vallabhadeva; Saduktikarnāmrta of Śrīdharadāsa; Sārñgadharapaddhati of Sārṅgadhara; Subhāsitaratnabhāndāgāra of Kāśīnāthaśarma; Subhāsitasudhānidhi of Sāyaṇa and, Subhāsitanivī by Vedānta Deśika.

UPADEŚASĀHITYA[edit]

Seeing the abominable deterioration of the moral standards in the society of their times, quite a few poets of the middle ages wrote works in a scintillating style which not only described the things as they were, but also as they should be. Such works may be classified as upadeśasāhitya. A few such works may be mentioned here: Kuttanīmata of Damodaragupta; Kalāvilāsa of Kṣemendra; Drstānta- kalikāśatakam of Kusumadeva; Kali- vidambana of Nīlakanṭhadīkṣita; Anyokti- muktālatā of Sambhu; and, Bhāvavilāsa of Rudrakavi

VYĀKARANSĀHITYA[edit]

The earliest references to Sanskrit grammar are found in the Gopatha Brāhmana (1.24) and the Taittirlya Samhitā (6.4.7). Even though Pāṇini (500 B. C.) was the most brilliant of the grammarians and his Astādhyāyī eclipsed the earlier works, he does refer to a number of his predecessors such as Apiśali, Kāśyapa, Gārgya, Gālava, Bhāradvāja, Sākatāyana and Sākalya. (See ASTĀDHYĀYĪ and PĀNINI.) Many schools of grammar appeared in the post-Pāṇinian period. However, of the six such schools, the one based on the Sarasvatikanthābharana of the Paramāra king Bhoja (11th century A. D.) became the most extensively used. Mention may also be made of the following works: Sañksiptasāra of Krama- diśvara; Mugdhabodha of Bopadeva; Supadmavyākarana of Padmanabha; and, Sārasvatavyākarana of Narendrācārya.

Conclusion[edit]

The Sanskrit language has been the repository India's history, culture, religion, sciences and socio-political values for several millennia. It is in the best interest of Indians to learn it, preserve it and propagate it. It is highly gratifying to note that several countries of the world - both in the east and in the west- are encouraging the study and research of Sanskrit through their centers of learning. It is but meet to declare that India, the motherland of Sanskrit, should in no way lag behind.

References[edit]

- The Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Swami Harshananda, Ram Krishna Math, Bangalore